Ivory-Billed Woodpecker: The Rise and Fall of the “Lord God Bird”

A natural history of the ivory-billed woodpecker

Ghost Birds

The ivory-billed woodpecker, the largest woodpecker north of Mexico and one of the largest woodpecker species of all time, is a bird that frequently comes up exclusively in the context of the question, “Are they still around?”

Federal officials have delayed officially declaring the bird extinct, though it's believed to have been gone for decades. However, many unconfirmed sightings have been reported in recent years, continuing to fuel the debate on their status.

But what do we really know about this remarkable and enigmatic bird?

The Ivory-billed Woodpecker

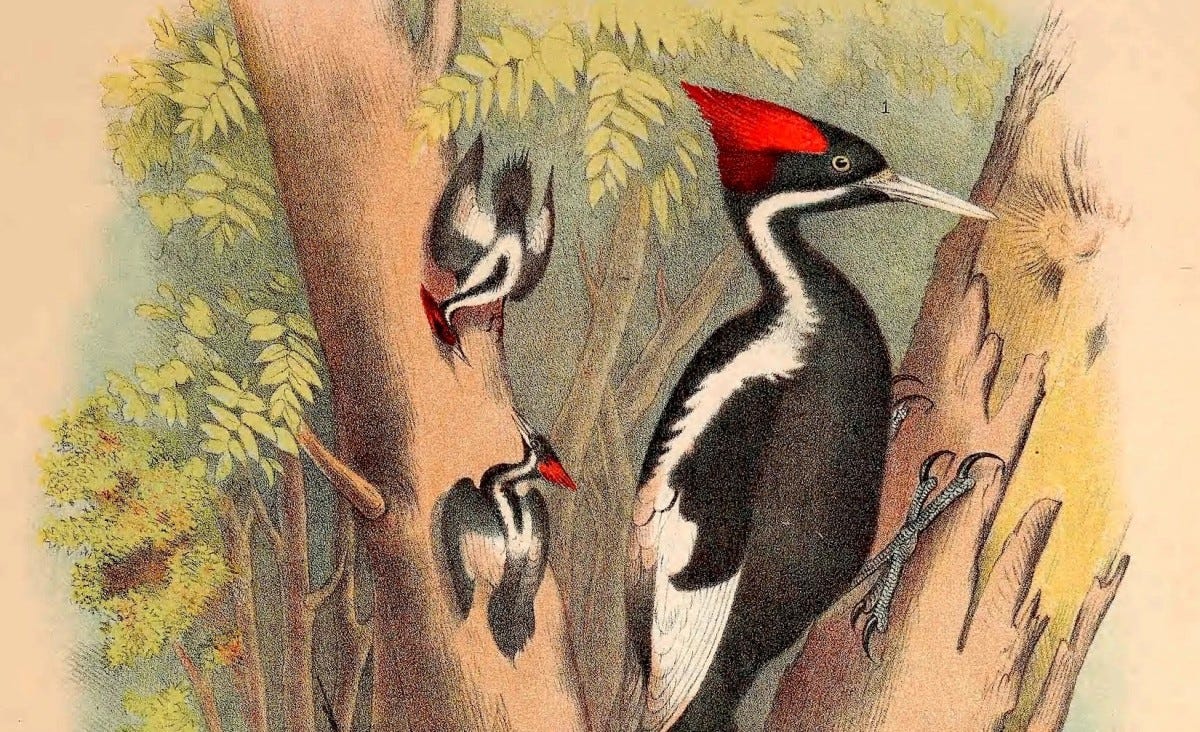

The ivory-billed woodpecker or Campephilus principalis—the genus name comes from the Ancient Greek for “caterpillar loving,” a nod to the bird’s preferred food not of caterpillars but rather beetle larvae—was typically 18-20 inches long with a wingspan of 29-31 inches. They were black and white with a pale “ivory” bill. The males had a red crest while the females sported a black one.

Recent genomic analysis indicates that the ancestors of this woodpecker diverged into two distinct populations during the Pleistocene epoch—when saber-toothed cats, Irish elk, and giant short-faced bears still roamed the Earth—leading to speciation, the evolution of new species.

One of these populations became the imperial woodpecker, the ivory-billed woodpecker’s even larger Mexican cousin, while the other evolved into the familiar ivory bill of the American South.

Though what constitutes its full historical range is still a matter of some debate, from records and the location of remains it can be surmised that the birds occurred in the swamps and bottomland hardwood forests that stretched across the deep south, and as far north as southern Indiana and southern Ohio.

Human Response to the Birds

This large and impressive bird inspired nicknames like “Lord God Bird”—supposedly due to what first-time observers of these woodpeckers were said to exclaim—and “King of the Woodpeckers.”

In 1731 English naturalist Mark Catesby was responsible for the first published description of the IBW, in which he called it the “Largest white-bill wood-pecker,” with a bill “as white as ivory”.

Catesby went on to note that the specimens of ivory-billed woodpeckers were in high demand and that Native Americans were known to pay three deerskins apiece for them.

For his part, American naturalist William Bartram, author of the acclaimed 1791 book Bartram’s Travels, said this of the species: “Picus principalis, the great crested woodpecker, having a white back.”

Scottish-American ornithologist and artist Alexander Wilson captured one of the birds because he wanted a live model for his painting. “This majestic and formidable species, in strength and magnitude,” he said, “stands at the head of the whole class of Woodpecker hitherto discovered.”

The woodpecker was deeply distraught by his confinement and fought hard to escape. In response, Wilson tied him to a table in his hotel room, where sadly the bird ultimately died.

According to Wilson, the captive ivory-bill “displayed such a noble and unconquerable spirit that I was frequently tempted to restore him to his native woods… He lived with me nearly three days, but refused all sustenance, and I witnessed his death with regret.”

French-American artist and ornithologist John James Audubon referred to the bird as “this great chieftain of the woodpecker tribe.”

As graduate student and eventual ivory-billed woodpecker expert James T. Tanner would learn during his three years of extensive research on the species during the late 1930s, the birds, though rare, were often killed when found. He heard many stories during conversations with locals about hunters who would shoot any ivory-bill they encountered.

One such man allegedly killed six in one day simply because he wanted to test out his new shotgun. Some supposedly shot the woodpeckers mistakenly believing that their bills were literally made of ivory and would net a large sum of money, while others merely wanted a closer look at the bird and chose this method for achieving that end.

A Highly Specialized Niche

Though we can never know for sure how many ivory-bills there were at the pinnacle of their success, it was certainly never a ubiquitous species and was instead confined to the forests and swamps which provided for its specific needs. And as David Quammen, author of The Song of the Dodo, succinctly put it: “Rarity is perilous.”

They had evolved to occupy a highly specialized niche, in which they strongly preferred the beetle larvae—specifically Buprestids (jewel beetles), Scolytids (bark beetles), and Cerambycids (long-horned beetles)—commonly found feeding on recently dead trees like sweet gums and Nuttall’s oak.

This was also why the ivory-billed woodpecker had such a strong bill—so that it could easily strip away the tighter-fitting bark of these freshly dead trees.

However, they were occasionally spotted eating other food, including hickory nuts, acorns, and the fruit of southern magnolia trees.

Cornell University Expedition

In 1935, a team that included Dr. Arthur Allen (founder of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology), a professor named Peter Paul Kellogg, and graduate student James Tanner set out on an expedition to locate and make sound recordings of as many bird species as possible.

This journey would take them across the U.S. and they would ultimately find and record the calls of approximately one hundred species of birds. By any measure, it was a huge success for the field of ornithology.

The group had a special interest in finding the ivory-billed woodpecker, a bird that was already considered to be likely extinct by earlier in the decade. Yet as they would soon find, this wasn’t the case.

The Singer Tract

In 1913, the Singer Manufacturing Company purchased 82,000 acres (at $19 per acre) of land, comprising bottomland hardwood forests and swamps, along the Tensas River in Louisiana, with an eye to future needs—oak for the wooden cabinets that housed their sewing machines.

However, they had no immediate plans for the land, which soon became known as the “Singer Tract,” and it was declared a refuge. Hunting was banned there and no trees could be cut without Singer’s approval.

The company entered into an agreement with the Louisiana Fish and Game Department, which put a game warden in charge of the tract of wilderness, to watch out for tree poachers or illegal hunting.

Due to its protected status, wildlife—including wolves, mountain lions, wild turkeys, deer, black bears, and countless species of birds—thrived there.

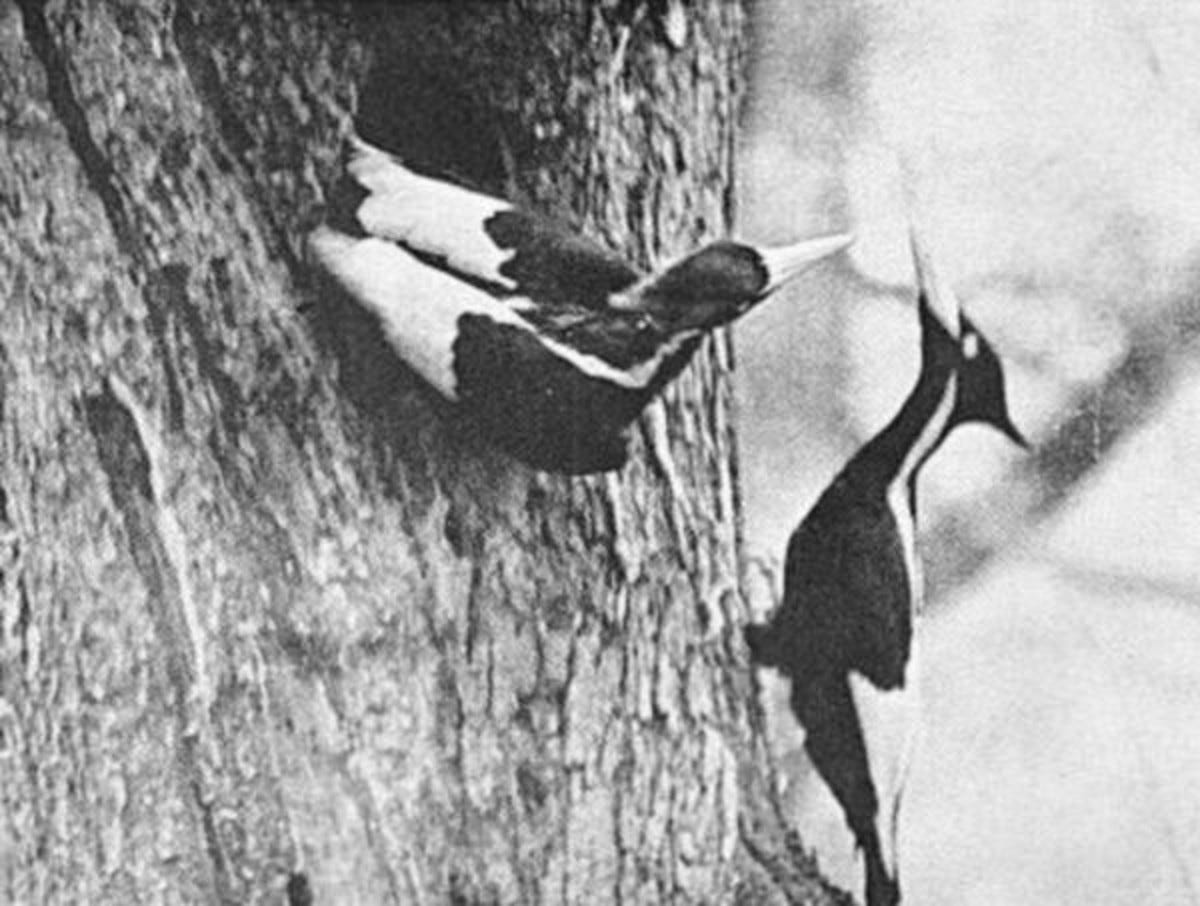

It was in the Singer Tract that Allen, Kellogg, and Tanner would discover the elusive ivory-billed woodpecker. They managed to capture both video and audio recordings of the birds, an invaluable contribution to science.

The woodpecker’s call had been variously described as kint, kent, yent, kuh, kak, and kient by those who heard it, but the Cornell team’s recording is the only one we have of it.

James Tanner’s Research

James Tanner, the person responsible for almost all of what we know about the ivory-billed woodpecker’s behavior, was dispatched to the southern states in 1937 to conduct an in-depth study of the elusive birds for his doctoral thesis. The aim was both to learn more about the species and find a way to save it before it was too late.

Over the course of three years, Tanner would travel 45,000 miles—speaking to locals in each spot he stopped at to find out if they knew anything about the ivory-billed woodpecker—and scour 45 sites in his search. Sadly, the only place he would ever locate them was the Singer Tract, namely in John’s Bayou and Mack’s Bayou.

He was able to observe three families of ivory-bills during his time there, learning that the males and females worked together as equals in raising their young. Interestingly, the birds were known to nest unusually early in the year. Tanner estimated that one of the eggs—and from his research it appears that they typically only laid one per clutch—must have been laid in February.

The historical record shows that the earliest known nesting for this species was on January 20th, 1880.

Unfortunately, there are still many unanswered questions about the IBW, including how long it took for a baby to grow from hatchling to maturity, how far the woodpeckers traveled, and their lifespan.

Tanner endeavored to discover the answers to these questions.

To that end, on March 6th, 1938, once the adult birds had left on a longer flight, he climbed up to the nest and banded the nestling—notably the only ivory-bill who would ever be banded.

This friendly and curious bird, whom Tanner dubbed “Sonny Boy,” soon jumped out of his nest and landed on Jack Kuhk, the local game warden who had accompanied Tanner. Several memorable pictures of the fledgling woodpecker were captured that day.

He would go on to see Sonny Boy a few times beyond this. In fact, the young bird was still following his parents around a year later when Tanner spotted him again during one of his visits.

He also located a lone male who would become known as “Mack’s Bayou Pete.”

All told, Tanner found and studied six different ivory-billed woodpeckers and concluded his research in 1939.

His doctoral thesis was published as The Ivory-Billed Woodpecker by the National Audubon Society in 1942.

Habitat Destruction

In his doctoral thesis, James Tanner relayed what he had learned about the Lord God Bird and called for sanctuaries to be created in order to save them. Sadly, he may have been too late.

Singer sold logging rights to the Chicago Mill and Lumber Company in 1939. Many of the trees so important to the ivory-billed woodpecker were now slated for destruction. The Singer Tract was no longer a refuge for the impressive bird.

Tanner never forgot about these fascinating woodpeckers and would travel back to the Singer Tract with his wife Nancy in subsequent years to look for the birds that he so admired.

During their 1941 trip, he found no male ivory-bills in the area (where were Sonny Boy and Mack’s Bayou Pete?) and only two females. December 28th, 1941, would prove to be the final time he would ever see a member of this species.

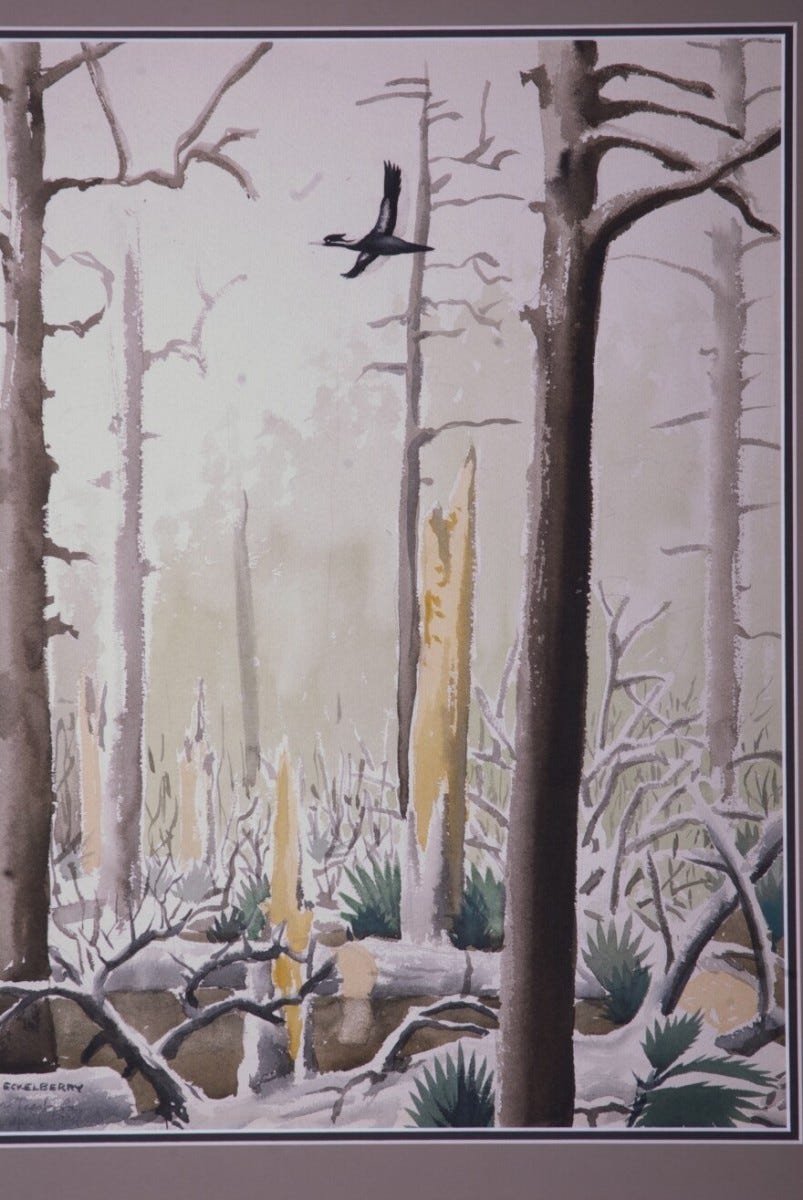

However, the last confirmed sighting of one wouldn’t occur until 1944. That year Don Eckelberry, a wildlife artist, was sent to document the last known ivory-billed woodpecker, a lone female. He spent almost two weeks observing and sketching her, which resulted in the haunting image of the female bird flying over a ruined forest that he would immortalize in one of his paintings.

Unfortunately, we have no definitive answers about what happened to Sonny Boy, the only ivory-bill to ever be banded, as no one ever reported finding him.

Are They Really Extinct?

Paul Hahn, author of the 1963 report entitled “Where Is That Vanished Bird?”, located 413 ivory-bill skins and mounts, as well as four skeletons, in museums across the world.

According to Birder’s World magazine in 2005, 21 noteworthy sightings of the ivory-billed woodpecker were reported between 1950 and 2004.

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology conducted an intense search for the woodpeckers, in response to reported sightings of them, from 2006 to 2010 to no avail.

It’s likely that most, if not all, of the sightings were of the pileated woodpecker, a smaller lookalike species.

Regardless, unconfirmed sightings continue to be reported periodically.

On September 29th, 2021, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service officially declared the ivory-billed woodpecker extinct.

On a positive note, a peer-reviewed study was published in the journal Ecology and Evolution in 2023, citing audio recordings, trail camera footage, drone video, and eyewitness accounts suggesting that the majestic woodpecker is still extant. The evidence was gathered in Louisiana and the precise location has been held back in order to protect the birds.

Even decades after the last confirmed sighting, there are many who hope and believe that this remarkable bird, always elusive, may still be out there somewhere.

If you would like to support my work and make a donation: Buy Me a Coffee

Sources

Bales, Stephen Lyn. (2010). Ghost Birds: Jim Tanner and the Quest for the Ivory-billed Woodpecker, 1935–1941. U Tennessee P.

Flores, Dan. (2022). Wild New World: The Epic Story of Animals and People in America. W.W. Norton & Co.

Einhorn, Catrin. (2023). “A Vanished Bird Might Live On, or Not. The Video Is Grainy.” The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/article/ivory-billed-woodpecker.html.

“Ivory-billed woodpecker.” (2023). Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ivory-billed_woodpecker.

“Mystery of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker.” (2016). BirdNation, https://birdnationblog.wordpress.com/tag/arthur-allen/.