Heath Hens: Booming Ben and the End of a Species

A brief history of a vanished subspecies of prairie chicken

Heath Hens

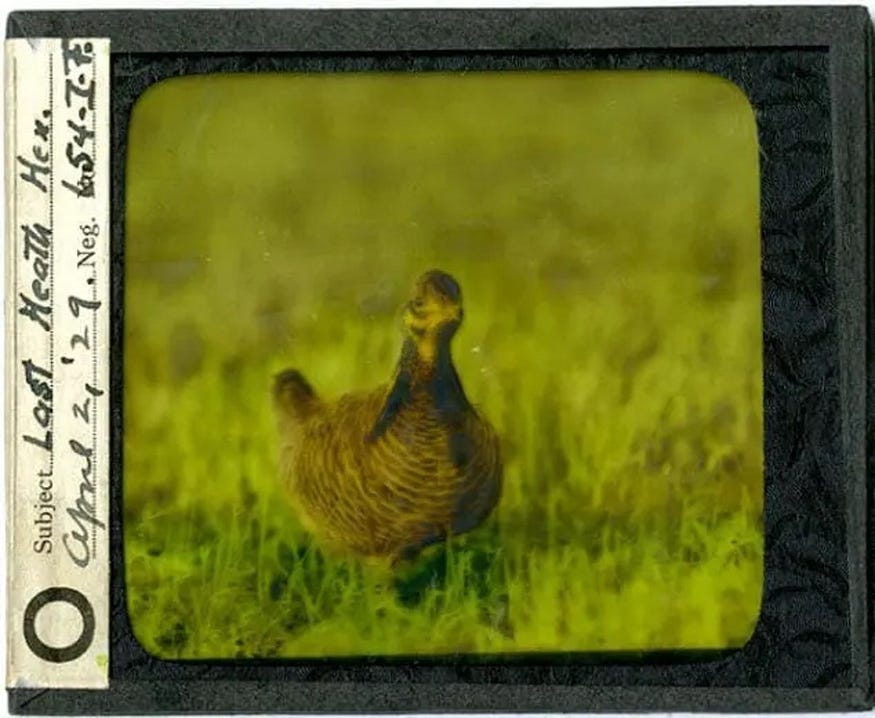

Heath hens (Tympanuchus cupido cupido) were once plentiful in mainland North America. These birds, closely related to greater and lesser prairie-chickens, were a common sight for settlers during colonial times and often provided them with an easy dinner.

The heath hen was even the subject of famous ornithologist and artist John James Audubon’s first commercial illustration, which was commissioned by a Philadelphia engraver in 1824.

But by the 1870s, the once ubiquitous species had become extinct on the mainland and only a small population of the birds remained on Martha’s Vineyard—until they, too, eventually vanished.

How did the heath hen go extinct? And could science bring the species back one day?

Tympanuchus

The genus Tympanuchus contains a species of grouse known as “prairie-chickens.” The name comes from the word “timpani” (a type of percussion instrument), referencing the booming sounds the males make during their mating display.

Conversely, the heath hen’s subspecies, cupido cupido, was named after the Roman god Cupid’s wings and was reportedly inspired by the appearance of the bird’s feathers.

These birds had a preference for heath barren habitat and their historical range extended from throughout New England down to Virginia, as well as a bit further west into states like Pennsylvania.

In terms of diet, they were opportunistic generalists and consumed a fairly wide variety of food, including clover, insects, grasses, berries (especially partridge berries, blueberries, and hayberries), seeds, crops, and sorel. Among the insects they ate were potato beetles (a common garden pest), grasshoppers, and crickets.

Come spring, the males would gather in open fields (or “leks”) to carry out their mating displays, which involved dancing (stamping and strutting) and making booming vocalizations to attract a mate. These distinctive sounds were made possible by the inflation of air sacs on either side of their neck.

Heath hens, on average, reached a size of around 17 inches long and 2lbs. Their plumage was reddish brown with thick dark bands.

Population Decline

Native Americans occasionally hunted heath hens. Their practice was to spread ashes on the lekking sites, which, after the males began their mating dance, had the effect of creating a blinding cloud around the hens, making it easy to approach and kill them.

Though, apparently, this wasn’t done often enough to cause any real harm to their numbers, as they were still quite abundant by the time Europeans arrived.

It has been hypothesized that the Pilgrims’ first Thanksgiving dinner—which took place in Plymouth, Massachusetts, in 1621—might have featured heath hen as the main course, instead of wild turkey.

Heath hens “were so common on the ancient bushy site of the city of Boston,” according to naturalist Thomas Nuttall (1786–1859), “that laboring people or servants stipulated with their employers not to have the Heath-Hen brought to table oftener than a few times in the week.”

J.H. Studer, author of Studer’s Popular Ornithology, described the bird’s flavor:

“The flesh is dark, having a gamy flavor, and, where not too common, is considered a great treat.”

Due to overhunting and habitat loss, the number of heath hens began to precipitously drop on the mainland, until they had been extirpated entirely. By the 1870s, the birds (approximately 300 of them) could be found exclusively on the island of Martha’s Vineyard.

Martha’s Vineyard History

As the story goes, English explorer and barrister Bartholomew Gosnold came across a small island off the coast of Cape Cod in 1602. He decided to name it “Martha’s Vineyard,” after his deceased daughter, as well as the wild grapes he found in such abundance on the island.

Gosnold and his men spent days following the coastline and eventually encountered Native Americans, with whom they traded before leaving.

Bartholomew Gosnold would be integral in the founding of both the Virginia Company and the colony of Jamestown (where he would die during a malaria epidemic in 1607).

The natives the explorer met on Martha’s Vineyard were the Wampanoag (“People of the First Light”). The Wampanoag and their ancestors had been living there for thousands of years before the arrival of Europeans. Their name for the island was “Noepe,” which means “Land Amid the Waters.”

After settlers made contact with the Wampanoag on the island, the Native Americans taught them how to do a variety of things, like planting corn, locating clay for brickyards, and how to catch whales.

Martha’s Vineyard became quite prosperous during colonial times and was successful in the fishing and farming industries, exporting fish, butter, and cheese by the boatloads.

To this day, many Wampanoag still reside on the island that was to become the final home of the heath hen, in the community of Aquinnah, as well as Mashpee on nearby Cape Cod.

By the late 19th century, Martha’s Vineyard was famous for having the last heath hens. These birds were beloved by many on the island and an earnest effort to help the species recover—notable for being one of the earliest attempts to save a species from extinction—was soon initiated.

Efforts to Save the Heath Hen

The enactment of a hunting ban coupled with the creation of “Heath Hen Reserve” in 1908 led to a significant rise in their population, which grew to around 2,000 birds. In the 1910s, observing these birds on their lekking grounds became a popular activity on Martha’s Vineyard.

Things looked hopeful for the species, which had begun to thrive again. Sadly, though, this was not to last and a tragic series of events would once again place them on the path of extinction—for the final time.

The habitat favored by heath hens was fire-dependent, meaning that periodic controlled burns are beneficial and prevent much larger and more destructive fires from occurring later.

However, fire ecology wasn’t well understood at the time and, due to this, a good faith attempt was made to prevent any fires from happening, which would inadvertently have disastrous consequences for the heath hen population.

On May 12th, 1916, a conflagration started and was quickly spread across the island by high winds, resulting in the burning of approximately 13,000 acres—roughly 20% of the island.

The Vineyard Gazette wrote:

“The fire wardens and their squads fought the blaze with backfires, or shoveled and plowed great furrows to be used as fire stops. But a shift in the wind or flying fragments of burning woods almost nullified their efforts. The fire stops made by the state along the crossroads proved entirely inadequate.”

The wildfire was responsible for killing around 80% of the remaining heath hens.

Their numbers would be further reduced by goshawk predation and a particularly harsh winter. Captive breeding efforts failed.

“Dissections after the fact revealed that the males’ testes had not developed for the breeding season,” wrote Matthew Kamm in The Life and Death of the Heath Hen, “possibly due to a lack of the green sorrel and clover that made up their typical spring diet, or possibly due to being restricted in cages and unable to perform their normal lekking activity.”

In 1927, there were 2 females and 11 males left. However, by the following year, only one heath hen remained—a bird affectionately referred to as “Booming Ben” by local residents.

Booming Ben

Unaware that he was an endling (the last of a species), Booming Ben went to his lekking grounds and performed his mating dance in both 1928 and 1929. Sadly, he fell silent after 1929, perhaps recognizing that there was no longer a potential mate to call out to. Yet he didn’t give up on life and continued to go about his days, eating and wandering through the fields and wooded areas.

In 1931, Ben was captured by professor and ornithologist Alfred O. Gross and gently fitted with two aluminum bands for identification—one reading 407880 and the other A-634024.

Gross noted how robust the bird appeared to be:

“The last Heath Hen is a splendid, well-groomed male…heavy, plump, and exceedingly strong and resistant with no trace of disease or external parasites.”

He went on:

“It is truly remarkable that this lone bird, subject to all the vicissitudes of the weather, to disease, and to natural enemies, has been able to live in solitude for such a long time.”

James Green, a farmer whose property Booming Ben frequented, grew to love the bird and looked forward to seeing him. But, in early 1932, Ben began to behave uncharacteristically, appearing wary and avoiding areas that he had previously enjoyed.

March 11th, 1932, would mark the final day that Green ever saw the heath hen, and it’s believed that he might have died not long after. However, Booming Ben’s body was never recovered.

Reports of a “somewhat ragged-looking” heath hen came in until July, but none of these sightings were ever confirmed to be Ben and some even turned out to be a female ring-necked pheasant.

Booming Ben was estimated to have been around 8 years old at the time of his disappearance—an incredible age for a prairie chicken, as they often survive only one year in the wild. His loss, as well as the extinction of his species, was considered a tragedy by many.

“Never in the history of ornithology has a species been watched in its normal environment down to the very last individual,” Gross poignantly remarked.

A heath hen statue now stands in the Manuel F. Correllus State Forest in West Tisbury—the former site of the bird reserve—placed in the area where Booming Ben was last spotted.

Could Science Bring Heath Hens Back?

A popular topic in the science community in recent years is de-extinction—bringing back some of our vanished species. But could this be done with heath hens? In theory, yes.

There are over 100 museum specimens that contain viable DNA, making it possible for scientists to recover the genome of these birds. The next step would be identifying their unique genes and then editing them into the genome of one of the heath hen’s closest living relatives—such as the greater prairie chicken—potentially allowing scientists to bring the heath hen back as a hybridized version.

While such a project is likely many years in the future, it’s encouraging to think that heath hens—and perhaps other extinct species—might return in some form one day.

If you would like to support my work and make a donation: Buy Me a Coffee

Additional Sources

Hope is the Thing With Feathers: A Personal Chronicle of Vanished Birds by Christopher Cokinos

(This article was originally published on Owlcation and was also boosted on Medium)