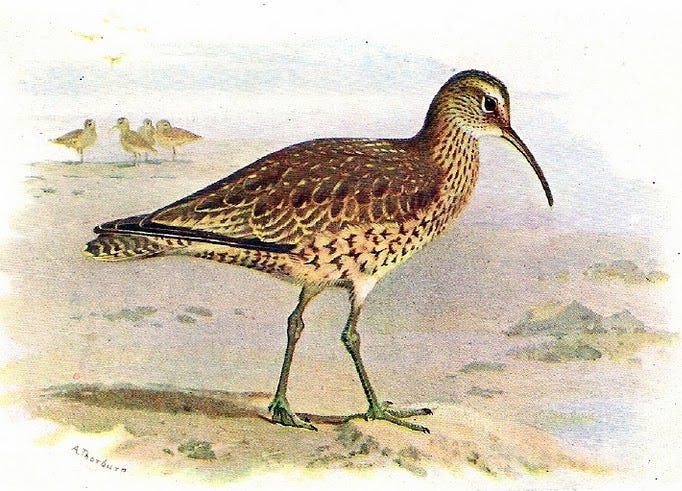

Eskimo Curlew: Portrait of a Shorebird

Flocks of these migrating birds once stretched for miles

Eskimo Curlews

The Eskimo curlew (Numenius borealis), once an abundant shorebird, has become exceedingly rare in the past century—or perhaps even extinct. The last confirmed sighting of the species took place on Galveston Island, Texas, in 1962.

However, unconfirmed sightings have been sporadically reported since, inspiring hope that these birds might actually still be around.

And though for decades there has been no definitive proof that they’re still extant, the Eskimo curlew is technically classified as “critically endangered,” not extinct. This is fairly unsurprising, considering there is an inherent problem in determining whether or not a species is gone—and this is that it is impossible to conclusively prove that an animal no longer exists.

While it might be the most plausible explanation, especially in the absence of anything that strongly suggests otherwise, it will always be theoretically possible that they still exist in small numbers somewhere, which is comforting in a way.

So might the Eskimo curlew still live on? Or are they truly gone?

Numenius Borealis

Belonging to the family Scolopacidae—a group that also includes snipes, woodcocks, sandpipers, and phalaropes—Numenius borealis had a range that extended from the Canadian Arctic down to South America.

The provenance of the genus name is something of a mystery. One theory is that it’s a Latinized version of the Greek noumenios, meaning “of the new moon,” which could be a reference to the shape of this curlew’s bill.

Conversely, it has been suggested that it might derive from the Latin numen—or “nod”—as the bird walked with its head tilted downward.

The specific name, borealis, is Latin for “northern” and refers to the location of their breeding grounds. The Arctic tundra making up part of their range also explains why they are the “Eskimo” curlew. Other common names for them include “little curlew,” “doughbird,” and “prairie pigeon.”

The species was described by German naturalist Johann Reinhold Forster in 1772.

These birds reached a size of up to 12 inches long, with a wingspan of around 27.5 inches.

Long-Distance Migrants, Market Hunters

This species preferred to make their nests, which were made with leaves or grass, in open areas on the ground. They had a clutch size of up to four eggs each year, with the eggs themselves being green with brown spots.

Their various calls are not well-documented, but some accounts described the birds as sounding bell-like.

Interestingly, the Eskimo curlew is believed to be one of the shorebirds spotted by explorer Christopher Columbus as his ship neared land in October 1492.

Their migration routes would take them from places like the Yukon and Northwest Territories down to as far south as the Pampas of South America for the winter. Similar to the passenger pigeon, they traveled in huge flocks. In the 1850s, there were numerous reports of flocks that extended for miles during the spring and autumn.

Eskimo curlews ate a diet that consisted of berries and insects such as snails and Rocky Mountain locusts. Because the birds were long-distance migrants, their calorie intake would increase for part of the year, leading them to put on a healthy layer of fat in preparation for a long journey.

Unfortunately, this extra fat also made them a popular market bird, which resulted in market hunters killing them in large numbers (as many as two million per year) during the late 19th century. At their peak, they had probably numbered in the millions, but after many years of merciless hunting the species appeared to be on the brink of extinction.

Additionally, like the Carolina parakeet, Eskimo curlews refused to abandon their wounded or dying and would instead go to them, which sadly made them easy targets for hunters.

Efforts to Save the Curlew

By the early 19th century, it had become clear that this bird—as well as many other species—was in trouble. Market hunting was finally outlawed in 1909. And the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, which was passed in 1918, aimed to protect migrating birds.

But was it already too late for the Eskimo curlew to rebound? Hunting wasn’t the only factor that made recovery difficult for these birds. Much of the grasslands they favored had been turned into farmland.

Furthermore, one of the insects they loved to eat, the Rocky Mountain locust, went extinct. It was once unimaginable that these grasshoppers could ever disappear. In 1875, they formed a record-breaking swarm—1,800 miles long and 110 miles wide—in Nebraska.

However, within a few decades they would be gone. The cause of their extinction isn’t known with certainty, but it has been speculated that plowing and irrigation, as well as being trampled by farm animals, caused them to lose a significant amount of eggs in a relatively short period of time. The final recorded sighting of a Rocky Mountain locust took place in 1902.

Galveston Island Sightings Renew Hope for Species

In 1962, two Eskimo curlews were spotted on Galveston Island in Texas. This was a cause for excitement to bird enthusiasts, and a photographer was able to capture several shots of the pair. These were the last confirmed sightings of the species.

One eyewitness never forgot the experience and even wrote about it later in life.

“There’s a chapter in my memoir in which I call it the bird of my life,” said Victor Emanuel. “For a birder who had seen this bird in field guides, which said it was possibly extinct, it was like seeing a dinosaur. It had a huge effect on me.”

The following year, an Eskimo curlew was allegedly shot in Barbados.

Then, two decades later, 23 curlews were reportedly seen in Texas. However, there was reason to question the veracity of this claim.

“Every season starting in June or July, I get a call with someone reporting an Eskimo Curlew,” explained shorebird biologist Bob Gill. “Invariably they are juvenile whimbrels.”

Jon McCracken, director of national programs at Bird Studies Canada, echoed this disbelief.

“It seems quite unbelievable to me that so many birds would show up on a single occasion, and not be seen ever again. It’s like verifying that there are UFOs out there without good solid physical evidence.”

Are They Gone?

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service concluded a five-year study in 2021, which found no evidence that the Eskimo curlew is still extant.

Yet sightings of the birds are still reported from time to time. In fact, dozens of unconfirmed reports have come in from Canada, Texas, North Carolina, New Jersey, Massachusetts, and Argentina in recent decades. And, while never officially confirmed, several eyewitness accounts from 1987 are regarded as reliable.

Though some believe that many of these birds are likely to actually be juvenile whimbrels, with whom Eskimo curlews share a strong resemblance.

So is Numenius borealis gone? Maybe. But there’s still a chance that there might be at least a small number of them out there and that one day someone will prove this.

If you would like to support my work and make a donation: Buy Me a Coffee

Sad, but very interesting. Great job!